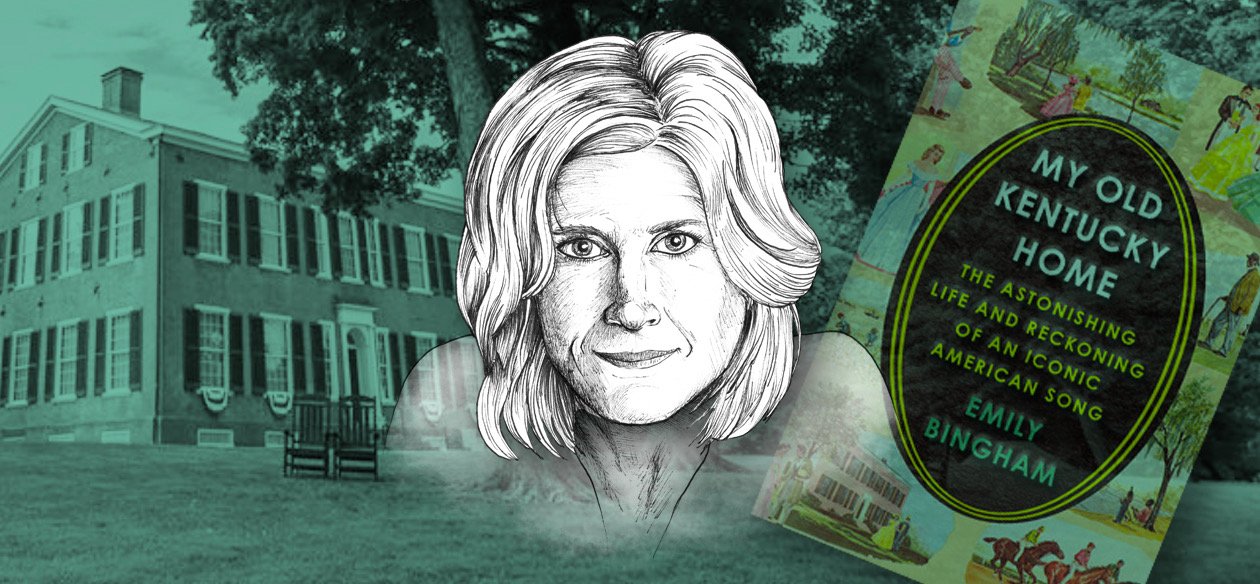

Emily Bingham Aims to Build a New Kentucky Home

The last time I witnessed “My Old Kentucky Home” performed wasn’t at the Derby. Back in August, on the eve of Fancy Farm, I attended the Annual Marshall County Democratic Bean Dinner in Western Kentucky. I showed up to see its headline speaker: Kentucky’s first Black senatorial candidate from a major party Charles Booker.

But before he or any other speakers on the bill would take to the stage, the crowd and I would stand for an unusual rendition of both “The Star Spangled Banner” and “My Old Kentucky Home.” After the performer asked everyone in attendance both to stand and join her in singing the National Anthem, she made the same request for Kentucky’s state song.

Candidly, I didn’t know the words to the song, so I just stood with my head bowed, equal parts reverent and embarrassed. When I managed to look up at what others in the room were doing, I noticed that Charles Booker also refrained from singing. A staffer would later tell me it was very intentional: “You know it was originally a minstrel song, don’t you?”

I’ve thought about this moment a lot, about how Stephen Foster’s 1853 song can continue to hold its power despite its legacy. To help make sense of the song and the different versions of American culture that propped it up, I read Emily Bingham’s My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song.

The text masterfully weaves the history of the creation of the actual song, the context of the social and political cultures that embraced it and transformed its meaning, and its still evolving legacy. Importantly, as Bingham notes, the song has almost always gained popularity as it’s whitewashed the history of chattel slavery and bolstered white supremacy.

Identifying Stephen Foster

In a way that has resembled “mind control” for Bingham, Kentucky’s state song “has a past informed by thousands of performances, enactments, critiques, and defenses that, over time, encapsulate the United States’ contradictory and contorted relationship to slavery and white supremacy.” By understanding the song’s past and the tradition it helped create more directly, we can also begin to disentangle these contradictions and look at the song for what it originally was: an ode to white supremacy.

Stephen Foster, as Bingham chronicles, came from a middle-class Pittsburgh family. A musically gifted but troubled man, Foster was best known for creating songs that would popularly feature in minstrel shows.

Generally, these performances centered on white men who, dressed in blackface, played on racist tropes and stereotypes to entertain white audiences. “These depictions and their wide acceptance by audiences did incalculable social and human damage,” Bingham writes. “Minstrel shows encompassed contradictory white supremacist notions of Black musical virtuosity and Black primitiveness.”

“Not for the first time and decidedly not for the last, white presumptions about Black behavior and bodies put money in white men’s (it was almost always white men’s) pockets even as they denigrated one race to help elevate another.”

Minstrel shows were massively popular throughout the nineteenth century principally because of their denigrating nature. Still, despite his established musical background in the tradition, Foster aimed to appeal to a more middle-class audience by making his music more appropriate for more genteel parlor room playing.

Although Foster never outwardly supported emancipation of enslaved Blacks or any abolitionist organizations, he based what would undeniably prove to be his biggest hit on the most provocative anti-slavery novel of the first half of the 1800s: Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Bingham identifies an important irony here. Even though the song depicts a family torn apart by slavery, it manages to romanticize and even defend the institution.

The Evolution of “My Old Kentucky Home”: From Minstrel Ballad to Lost Cause Lament

“I already knew that no small number of historians since the end of the Civil War had behaved as Foster did, telling our national story in ways those in power could make comfortable sense of, and I wanted to do something different.”

The 1932 Kentucky Derby, courtesy of The Courier-Journal

The song before the Civil War – and for a good deal of time after it – was often performed in minstrel contexts, again with white men dressed in blackface. And as the country transitioned out of Reconstruction and into another era of economic, social, and political disenfranchisement for Black Americans, the song would begin to take on new meanings that largely reflected this culture.

“It smoothed the path to a cross-sectional American reunion,” Bingham writes, “defined exclusively to meet white needs, feelings, and desires, a unity that self-consciously discriminated against its Black citizens.” Throughout the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth, “My Old Kentucky Home” would continue to connote a Lost Cause mythology.

For this reason, the song only gained more traction. It wasn’t until the 1930s that the song became enshrined in official Kentucky Derby proceedings. And as the song soared in popularity, whites grew comfortable with it for all the wrong reasons. “Amid mass immigration, industrial strife, women’s suffrage, world war, and racial unrest,” Bingham states, “the classic tune, a white tonic spoken through a supposedly Black tongue, evoked rural safety, gentility, and a lost world where Black people knew their place.”

How Emily Bingham’s Family History and “My Old Kentucky Home” Intersect

Emily Bingham’s historical text ultimately succeeds because of its methodically anti-racist approach. In addition to its exhaustive investigation into the song and the political and cultural contexts it came out of, Bingham also weaves her own family’s history to highlight how challenging and necessary this kind of work is.

“My grandfather’s grandfather operated a classical academy not far from Chapel Hill,” she reflects, “and held fourteen people in bondage.”

Courtesy of Emily Bingham

An ex-Confederate with formal allegations of “Ku Klux Klan vigilantism,” Robert Hall Bingham’s name adorned one of the University of North Carolina buildings where Emily Bingham studied in graduate school. Even though she knew she was related to him, she didn’t understand who he was until much later in her life.

“Year in, year out,” she states, “he educated young men in Latin and white supremacy, teaching them to honor the Lost Cause and uphold the racial order his violence helped establish.” It’s in blunt and vulnerable moments like these that Bingham lays out the goal for her work most clearly. As Americans, we have a responsibility to understand the ugly and brutal history of how chattel slavery helped form our country. And as Kentuckians, we share a responsibility in scrutinizing cultural artifacts that have often functioned to whitewash that history.

Positioning “My Old Kentucky Home” in a Changing World

So then, “[w]hat should we do with this song, this legacy?” Bingham asks. The answer should ultimately not come from her, she writes, but from the people who have been historically marginalized by this song and the culture it has reflected.

“The time has come to let Black voices be heard and for white people to be guided by them.”

The song has succeeded now for nearly two centuries in muddying the waters about its central tension. “[R]ace-based slavery, its subject, slipped out of the minds of generations of Americans. The singing is a nation’s song to its white self.”

As far as one outcome goes, Bingham wants Kentuckians to get ready to let the song go. Even for those who maintain an enduring appreciation for it, letting the song lose its significance can send a message all on its own.

“[G]iving up something we love can be a sign of love,” Bingham offers. “Relinquishing ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ signals regret for wrongs this single melody encapsulates. It is a gesture that seeks forgiveness and chooses compassion over tribal satisfaction, no matter how innocuous that satisfaction has felt.”

Join Kentucky to the World on October 23 for our program The State of Song: “My Old Kentucky Home” Faces a Changing World at the Kentucky Center’s Bomhard Theater. In addition to live musical performances and audience participation, Emily Bingham, Harry Pickens, Ben Sollee, and Hannah Drake will hold a conversation that examines the song’s problematic roots, its legacy, and its modern disconnect.