SHELLY ZEGART: THE GREAT AMERICAN QUILTER OF COMMUNITY

Don’t let the headline fool you. Shelly Zegart has never picked up a needle and thread and has no interest in ever doing so. It could be because she never sits still long enough to meticulously craft something like a quilt, but my theory is that it’s because Shelly is a master at recognizing and elevating the talents of others. It’s been the common thread of her life.

Shelly founded Kentucky to the World but she’s more widely known for her work to elevate the art of quilts, a passion that ended up defining over three decades of her life. Shelly has recently received the highest honor in Kentucky for this kind of work, but more on that later. She’s an absolute force of nature packed into a small frame and to really tell you this story, we need to start at the beginning.

A WOMAN’S PLACE

Shelly caught the collecting bug early in life when she was growing up in Pennsylvania. She fondly recalls antiquing with her mother during her childhood as the spark that lit the fuse for her lifelong dedication to collecting art, but she also became a collector of stories. Her mother, Thelma, was a pianist who travelled the East Coast with an all female band and made appearances on the radio in the 1930s. Her father, David H. Weiss, was a Jewish refugee from Czechoslovakia who served as a Pennsylvania state representative for 6 terms before being appointed as an assistant district attorney and finally being elected as a judge, a position he held until only a year before his death in 1979. From her mother, Shelly learned that a woman’s place is wherever she chooses to place herself. From her father, Shelly learned that the work of an advocate is never finished.

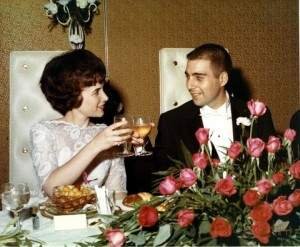

Shelly married Dr. Kenneth Zegart on June 17, 1962 with a $10 wedding band that he still wears on his ring finger all these years later. One can never know where life will take you when you step up to the altar and make a lifelong commitment to another person, but these two are a masterclass in growing together. Even in the ‘60s, Kenny was well aware that he married a woman who would never be content to define her life as only a doctor’s wife.

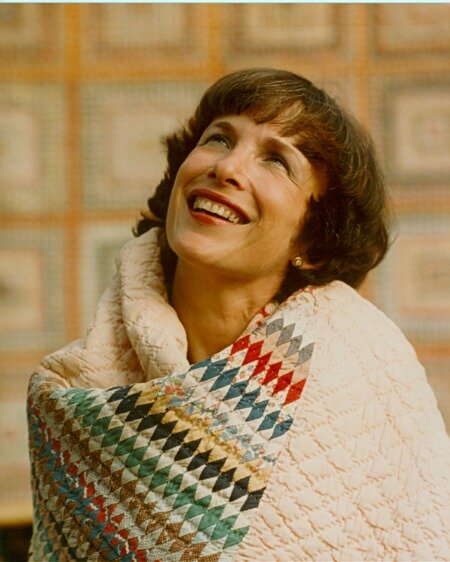

(L-R) Shelly and Kenny Zegart on their wedding day in 1962, Shelly and Kenny Zegart today

Kenny is a renowned and respected OB/GYN in Louisville, running his practice and advocating for women’s rights for almost as long as he’s been married to Shelly. His personal affect is much more reserved than that of his wife -- last summer he described her to me as “the tornado beneath his wings.” But Kenny is still a character all his own; a doctor who loves riding his Harley and being a hobbyist magician. Shelly often repeats one of Kenny’s go-to mantras when deadlines are approaching and her inbox is exploding, “if it’s not life threatening, it’s only details.”

Shelly never lost her deep appreciation for collecting art and when the couple started building a contemporary home to fill with contemporary art in the late 1970s, they hit a rare snag. Shelly started snatching up cutting edge pieces from emerging artists that reflected the social upheavals of the time and Kenny just wanted to come home to rooms that felt a bit more...relaxing.

Around the same time, a mother from the school their daughters attended told Shelly that she needed to meet Bruce Mann (no, not the one married to Elizabeth Warren). Bruce had been collecting quilts and making regular trips to New York City and Los Angeles to sell these quilts to collectors who treated them like art pieces.

Shelly was intrigued. She joined Bruce and a small group for tea one night and together, they went through his collection. When she went back home later that evening, Shelly could barely sleep. Her mind was racing with questions: Why are these pieces so inexpensive? Why are the makers anonymous? Why isn’t this considered art?

“Visions of quilts were practically dancing in my head.”

(L-R) Shelly Zegart in 1982 for the Kentucky Quilt Project, in 2017 by Christine Mueller for StyleBlueprint and in 2020 with her Folk Heritage Award

WHY QUILTS MATTER

Shelly couldn’t shake the feeling that the exclusion of quilts from contemporary art was actually rooted in a tale as old as time. At the time, Shelly was the chair of Louisville Visual Art, a role that gave her a deep insight into the process and struggle of visual artists. Quilts are traditionally made by women in the home for use in the home. By contrast, the art world has traditionally been dominated by men obsessed with the importance of their own personal abstractions. But if collectors in large cities were purchasing quilts to use as art, where was the recognition for the artists? Were quilts merely a craft when laid upon a bed? Does a quilt only become art when hung on the wall?

Shelly was hooked. Something about quilts being “othered” in the world of elite art spoke to her memories of being on the outside in the small Pennsylvania community where she spent her formative years as part of one of the few Jewish families in town.

It wasn’t long before Shelly started amassing her personal collections with Kenny by her side visiting antique stores and flea markets to hunt for treasures, another familiar call back to her youth. The bold contemporary art in her home was gradually replaced by colorful quilts draped among her warm-toned, off-white walls. Kenny certainly found this aesthetic more relaxing and when he brought quilts in to decorate his OB/GYN practice, he realized that they may be the first pieces of art created by female makers to be hung on the walls of these rooms that were filled with women all day everyday.

On his way to California with a van full of quilts in November of 1980, Bruce Mann was tragically killed in a car accident. Left reeling with shock and grief, his close friend Eleanor Bingham Miller, a prominent Kentuckian, film producer, philanthropist and quilt collector, brought one of Bruce’s ideas to Shelly: find a way to document Kentucky quilts, their makers and their stories. Shelly agreed, but like all things she takes on, she wanted it to be big.

Relying on input from trusted scholars and friends, the original idea for a catalogue, exhibition and eventual center for American Quilts quickly shifted towards something more personal and accessible. The process of gathering stories from quiltmakers around the state grew exponentially as word travelled. It soon became clear as buzz about the project grew, this work had threads stretching far beyond Kentucky that could not be ignored.

After all was said and done, the project that Bruce started in spirit known as The Kentucky Quilt Project was the catalyst for the documentation and preservation of the history of over 200,000 quilts to date, work that continues to this day. In 1982, when the Kentucky-specific catalogue was released as part of a travelling exhibition of Kentucky quilts by The Smithsonian, over 25,000 copies were sold. By the 1990s, quilt projects from different communities, regions and countries were joining the initiative to be combined into a comprehensive index that is now an accessible resource housed at Michigan State University.

But, of course, it didn’t stop there. The quilts themselves aren’t the whole story. They needed to figure out a way for the questions that kept Shelly up at night all those years ago to be answered and showcased for everyone to see. The idea of a documentary was born. Using her network of scholars, writers, and artists of every kind, a nine-part documentary series was produced called Why Quilts Matter: History, Art & Politics. Shelly then brought the project to Craig Cornwell at Kentucky’s PBS outlet, KET, who put his enthusiasm into getting the documentary picked up by a PBS affiliate network to reach an even wider audience.

A GOVERNOR’S THANK YOU

Folks, believe it or not, all that background is just the tip of the iceberg. This story would be the length of a novel if we tried to cover everything Shelly has done to elevate quilting as an art form and honor the artists who make them by name. We’re telling you this story now because Shelly has been honored with The Folk Heritage Award for 2020, a prestigious Governor’s Award in the Arts by Governor Andy Beshear, for her work that spans across decades and geographies.

“This recognition is one to which ANY artist, arts advocate, or arts presenter of significance in Kentucky aspires to. My Governor’s Award in the Arts brings the extraordinary vision and aesthetic achievements of Kentucky quilt making to the attention of the public, and respects and celebrates the medium of quilting as a form of artistic expression”

A few years before she finally received this immense nod of appreciation, she stepped back from her role in the quilting world, always keeping a loving eye on it from a distance. The Art Institute of Chicago acquired The Zegart's private collection of quilts to inspire future generations of textile artists in 2001. The combined records of The Kentucky Quilt Project, the Alliance for American Quilts, and personal files belonging to Shelly were donated to the University of Louisville. Just this past year, Shelly donated her nearly 800 volume library of quilt and decorative arts publications to the Western Kentucky University library thanks to her decades-long relationship with the university’s museum. Next on her list is getting the original interview footage from the documentary entered into the Nunn Center for Oral History at The University of Kentucky. To Shelly, it would be a disservice to the work and its potential to continue educating for generations to come if it were all stored in one place.

But, stepping back and securing the preservation of her collections in institutions of higher learning only gave her more free time. And when Shelly finds herself with free time, it never lasts for very long.

KENTUCKY TO THE WORLD

Anyone who has spent more than 5 minutes in a room with Shelly can tell you that you never know what will spark her to dive into a rabbit hole with gusto. She’s embarking on her 80th year of life with more curiosity, energy and enthusiasm than anyone I’ve ever met. Her story is still being written.

Shelly’s daughter, Dr. Amy Zegart, is also an internationally renowned expert. In stark contrast to her mother’s interests, Amy has focused her career on international relations, primarily concerning national and cyber security issues. Before becoming a professor at Stanford University, she was already contributing to countless books and articles. She was even recently featured in an HBO Documentary. About a decade ago, Amy was a professor at UCLA and was giving a talk to The Pacific Council on International Policy. Here, in this room full of some of the brightest minds in the country, a man stepped up to the microphone when it was time for the Q&A portion of the evening and said, “Amy Zegart, I grew up a block away from your grandfather’s drugstore on the corner of 7th and Oak in Louisville.”

Zegart Drug Store in 1992 from The Courier Journal

This story, of course, sent Shelly reeling. The man was African American and she knew this was an important detail because Zegart Drugstore was the first lunch counter in the city of Louisville to open its dine-in services to people of color in the 1960s. Instead of quilts dancing in her mind, she was now going through a slideshow of all the Kentuckians she had encountered in her travels around the world curating, appraising and selling quilts. Like her daughter and this man at the microphone, these people were extraordinary and affecting the world in some way, but no one thinks of them or these kinds of stories when they think about Kentucky. Kentucky is the state without shoes, the people that consistently vote against their own interests; the place that is so backwards, its very name has become an adjective to describe the worst face of America.

In the same way Shelly couldn’t let quilt makers fade into the anonymous ether of history while their work hung in museums, she couldn’t let herself sleep on this thought knowing she had the power to do something about it. The rabbit hole had been opened and she was plummeting headfirst into starting a brand new cultural nonprofit as she entered her 70s.

Shelly Zegart introducing Chuck Brymer at the Brown Theater in conversation with Maggie Harlow in October 2018

If you’re reading this story, you’re already on Kentucky to the World’s website where you can learn everything about our organization from our speaking series to our student program, video work, storytelling, illustrations, installations and more, but you won’t find as much about the woman who started it all and keeps a dizzyingly full calendar every week to keep it going.

Before this award, we never knew when the right time to tell her story, or even a part of it, would come. It’s every bit as rich and interesting as anyone we’ve featured on stage or in any other work we’ve produced. With any luck, maybe someday soon, we’ll convince Shelly to sit still long enough for our camera to capture all the stories we haven’t heard yet.

Kentucky’s most prestigious honors in the arts, the Governor’s Awards in the Arts, will be presented at 11 a.m. EST on Jan. 26 on the arts council’s Facebook page and YouTube channel.

To keep Shelly’s vision going, please consider donating to our organization and following our storytelling on Facebook and Instagram.